I am listening to the podcast 372 Pages We’ll Never Get Back. In episode 9-16 they discuss Armada.

372 Pages We’ll Never Get Back

Real or fanfic

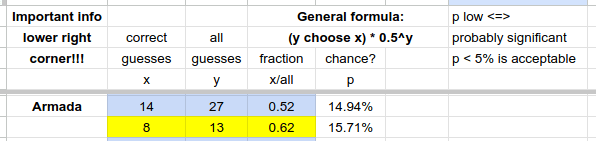

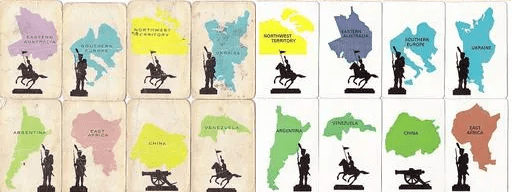

The spreadsheet  !

!

Summary of important advice

Consistency, continuity.

- Yawnsville the young man said.

- There’s an important difference between young Clark Kent and young Luke Skywalker?

- Claiming a group of real people made a game, when they don’t have the skills.

- The reasonable people are also villains.

- Mom uses a lot more time than is possible.

- The keying of a car is (not) very visible.

- Feels Star Wars fandom is embarrasing, then immediately forgets it.

- Claiming Edge of Tomorrow and Avatar can be crossed in a meaningful way.

- Being surprised when the same thing happens again.

- Humans are just apes. Oh wait, we’re not.

- Going from being shallow to caring deeply about the planet.

- Being in a hurry, but waiting for the other guy to turn around a corner.

- Anachronisms.

- Weak jokes, big laughs.

- People have learned something earth shattering, and they behave normally.

- Zack thinks some sf movies are bad?

- To my surprise I did something, I’ve done many times before.

- Is it power leap or power jump?

- Rocky Balboa does not sound like a person from Philadelphia.

- He detects irony, but it’s also lost on him.

- Dad had psychological issues, but wasn’t fired.

- Star Trek and Wars are important, but neither are really about aliens invading Earth.

- Admiral Akbar famously IDENTIFIES traps.

- Happily nodding while so many people just died.

- It makes no sense, I understand it perfectly.

- Society is mentioned, but it was actually 3 people.

- The swastika in the beginning was stupid, the aliens are smart.

Be exciting. Have stakes.

- A lot of pages, almost no plot.

- A list of years and events.

- Boring controllers.

- A fictitious ad.

- Someone playing a game.

- An unboxing.

- Battle cry: Let’s do diz.

- Show, don’t tell.

- But I’m agnostic! Simply don’t mention it.

- Lengthy recap of battle.

- Big news, father is alive, and it’s just said, dryly. Unforced error.

- Pregnant pause + stand for an awkward beat.

- Stereotypes.

- Repetition of phrases. Glance. Enormous x 2 in 1 sentence. Video.

- A list of snacks.

- All the letters from dad are included. No surprises.

- Description of battle, not engaging.

- Boring: navigating through menus.

- Repetition of words. Contorted (face). That playlist.

- Cliché ending.

Flow. Chekhov’s gun.

- Lex ex machina.

- Heavy or clumsy foreshadowing.

Originality.

- Flat out stealing Terminator.

- Stealing valor. Quotes by great people.

Realism. Being human.

- Eating 1 pop-tart?

- 18-years old and spitballs.

- Boy finds stack of video games, reads diary.

- Boy is satisfied with explanation for how dad died, but then turns 10.

- 10-years-olds have guilty pleasures?

- How many back to back to back viewings?

- The government controlled the ENTIRE video game industry?

- Dumb joke amused him EVERY TIME.

- Children like being bored by adults.

- My mom is insanely hot.

- My mother would protect me with heavy weaponry.

- Close to graduating high school, but has no plans.

- Just teenagers in general.

- Defending against aliens isn’t a team sport?

- The aliens move in very predictable 4/4 rhythms.

- Out of body. I heard myself gasp.

- That Hollywood plan was bad.

- High school seniors know they have father figures?

- Zack’s eating meatloaf, mom tries to slow him down every few minutes.

- A very long line in a conspiratorial voice.

- The voices of Sagan and James Earl Jones are wonderful/evil.

- Everything is either memorized or almost forgotten.

- Synchronized screaming.

- There’s a standard Nintendo controller?

- “Boom!” the 18-year-old said.

- Emotions bouncing around.

- Zack destroys a valuable ship, and the admiral is playfully sarcastic.

- Oh, and your father is a crybaby, said the admiral.

- The attack is in 5 hours! Also, here’s a uniform.

- Token Asian.

- A talks, all the time B is chuckling.

- People taking forever to recognize known motion.

- Zack doesn’t recognize praying.

- Very disdainful towards religion.

- Debbie has no answer to an attack on her religion.

- He missed that he might die???

- Feeling like a list of things.

- Everybody’s afraid, but father is delighted.

- Suddenly we’re in a hurry.

- Isolated people doing fine and making jokes.

- Being very surprised that father and son look alike.

- Suddenly sounding like Wodehouse.

- Every second counts and there’s time to talk hobbies.

- Soldiers shouldn’t have time for hobbies.

- You got my reference. Goofy grin.

- Dad’s mood swings.

- Zack can interpret all expressions.

- The admiral is very informal.

- Zack can identify fine bone china.

- Zack knows his own little tics.

- Even the new guy has given up on an error he just heard for the first time.

- The 3 top guys think there might be a conspiracy?

- Why all the secrecy?

- It doesn’t make sense dad makes this joke. Everybody makes the same kinds of joke all the time. Everybody’s the same person.

- Keep the war on drugs going until this gamer weed is perfected.

- Everybody’s so horny.

- How did Lex get promoted that fast?

- Gallows humor isn’t a well known word?

- Not checking the gym for people before shooting the roof.

- Long fingers. (Zack’s mom.)

- “Is that a tricorder?” End scene. (Was that a joke?)

- Being impressed by HD. On a small screen.

- Screaming for a long time.

Variety.

- New book, exactly the same style.

- Spitballs in school, cliché.

- A lot of Star Wars references.

- 2 Star Wars references close together.

- Repetition, cyclopean.

- Everything is instant. Everything is a million. Everything is exactly like… Make it smaller.

Details: not too many, not too few.

- Making a subtle reference, then immediately saying more.

- Excalibur, too much.

- Nobody wondered whether you lived close to school.

- Nobody wondered about eyewitnesses.

- An avatar controlling a drone, hard to visualize.

- Explaining what a taunt is.

- Revealing an incident, that was easy to guess.

- Comparing a shape to Arecibo, not very well known.

- Bad physical descriptions. Hard to imagine.

- When did they see the shuttles? When they were there.

- Oh, it’s your first moon quake?

- Rushed chapters, abrupt ending.

- A lot happens in 1 sentence, could be a separate book.

- How rankings work.

- And that was all it took.

- Seconds later: Reports are coming in.

- In 1 sentence: Clean abundant energy. Cures for cancer.

POV. Tone.

- … as it came to be known. When is the narrator?

- The narrator doesn’t know what is going on.

- Calling something a fun fact, when it’s not fun. And during a serious section.

- Comparing a battle to Christmas lights, popcorn and beer cans. Not very battle-y.

Use words and phrases correctly.

- The distant horizon.

- Using the same unusual word in 2 consecutive sentences.

- How should sobrukai glaive be pronounced?

- Cold pop-tarts are raw?

- The retro outfit was retro from day 1?

- What’s a Garp phase?

- Wanderlust.

- An actor nails a role, that was original.

- We went to their moon AND we have the home team advantage.

- It looked exactly like (what it was).

- I had never been so glued to a screen.

- People of Europa = Europans, confusing.

- Calling something a power leap.

- WTF. I nodded in agreement.

- … power lines like Godzilla. Mangled sentence.

- Almost as if. Which I actually had. (It only feels like a simulation.)

- I wish we’d met a long time ago, said the teenager.

- … but … Not contradictory.

- Wrong name, book of revelations.

- Seeing 20/20 out of the corner of his eye.

- Radiant doesn’t mean that.

- How to write out the Close Encounters melody.

- Not just using the word “said”.

- Mom was FOND of pointing out his gaydar was broken, OFTEN.

- Consistently calling a ship shaped like a dodecahedron a dodecahedron. It had 3 names!

- Being reminded of something that is exactly the same.

- Blushing visibly.

- Gross:

- Sired.

- Woman described in a creepy way.

Ep. 9

Review or review, 9:20

- Mike guessing

- RP1 ❎ Armada ✔️ RP1 ✔️? Armada ✔️ RP1 ❎

Real or fanfic, 19:57

- Mike guessing

- Fanfic ❎ Fanfic ✔️

Mike wants to some day do an Ernest Hemingway contest, just for Cline.

Ep. 10, ch. 1-3

Don’t do this

- In general: the style is painfully similar to that of rp1.

- A lot of pages and almost no plot.

- Distant horizon. Unnecessary word.

- Using the same word in 2 consecutive sentences.

- Yawnsville. Are you Fonzie?

- The sobrukai glaive. Pronunciation? Jerry Lewis!

- Eating 1 pop-tart?

- Cold pop-tarts are raw?

- Making a subtle reference and then unsubtling it.

- The retro outfit was retro from day 1?

- Spitballs. Clichés. Sounds too young.

- Excalibur, too many details.

- Answering an unasked question. Distance between school and home.

- Saying there’s an important difference between a young Clark Kent and a young Luke Skywalker.

- What’s a Garp phase?

- Sired. Gross.

- Boy finds a stack of games and reads a diary instead.

- Boy thinks a few details of father’s death were enough, but then he turned 10.

- Literally a list of years and events. Boring. No comments.

- 10-year-olds have guilty pleasures?

- How many back to back viewings, doing nothing else?

- The government controlled the ENTIRE video game industry?

- Wanderlust?

- That the tie fighter is involved in the naming AND LOOK of the Thai restaurant? Absurd.

- Dumb joke amused him EVERY TIME.

- Children like being bored by adults?

- Play a game where an avatar controls a drone.

- Boring controllers. And an ad for a fictitious store. Someone playing a game. And then an unboxing.

- Claiming a game was made by real world people without the needed skills.

- Stealing too much: This is Terminator.

Running gags

- Hauling ass?

- Rush is back!

Oops.

- No, the episode isn’t 6 hours long.

Real or fanfic, 27:00

- Mike guessing

- Fanfic ✔️ Real ✔️

Ep. 11, ch. 4-7 (until phase 2)

Don’t do this

- My mother is insanely hot.

- My mother would protect me with heavy weaponry. Really?

- The reasonable people are depicted as villains. Like his grandmother who didn’t like, that his mother dated a loser.

- His mother works, goes out to dance and watches a lot of television. When?

- He’s close to finishing high school and have no plans?

- Self awareness without taking action. Being embarrassed by his Star Wars fandom, but then keeps talking about it lovingly.

- Assuming people don’t know what taunts are.

- Not accurately depicting teenagers now.

- An actor nails an original part.

- Defending against aliens isn’t a team sport?

- We went to their moon AND we have the home team advantage.

- Layers of simulation. Hard to picture.

- Detailed description of a video game session.

- Battle cry: let’s do diz.

- The aliens move in very predictable 4/4 rhythms.

- The keying of the car is very noticeable but also not.

- Revealing an incident, that was very easy to guess.

- There’s no doubt, but eyewitnesses are important.

- How do we cross Edge of Tomorrow and Avatar?

- I heard myself gasp.

- He’s surprised by the spaceships, again.

- The Hollywood plan was bad.

- High school seniors know they have father figures?

- His real name is… Yawn.

- It looked exactly like what it was.

Running gags

- A lot of back to back viewings.

- Insert hot before mom.

- Rigs.

- Observing oneself doing stuff.

- It seemed like an eternity. (But it wasn’t.)

Oops.

- “Where they live” only means something literally?

Real or fanfic, 37:22

- Mike guessing

- Hint: 1 is real

- Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ❎ Fanfic ✔️ Real ❎

- Conor guessing

- Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ✔️ Real ✔️ Fanfic ✔️

Ep. 12, ch. 8-11 (to 12)

Don’t do this

- Humans are just apes. Oh, wait, we’re not.

- Going from being shallow to caring deeply about the planet.

- Clichés.

- Zack’s eating meatloaf, mom tries to slow him down every few minutes.

- A very long line in a conspiratorial voice.

- Make sure references are crystal clear.

- A lot of Star Wars references.

- Being in a hurry, but waiting for the other guy to turn around a corner.

- Woman described in a creepy way.

- Anachronisms.

- Weak jokes, big laughs.

- People have learned something earth shattering, and they behave normally.

- Repetition, cyclopean.

- The voices of Sagan and James Earl Jones are wonderful/evil.

- Everything is either memorized or almost forgotten.

- Show, don’t tell.

- I had never been so glued to a screen.

- Zack thinks some sf movies are bad?

- People of Europa = Europans, confusing.

- Synchronized screaming.

- There’s a standard Nintendo controller?

- But I’m agnostic! Simply don’t mention it.

- Calling something a power leap.

- WTF. I nodded in agreement.

Running gags

- Pendergast.

- Not in control of ones own faculties.

- Hot mom.

- Clinean: What if I won’t do it? You’ll be drafted. I will? No.

- Rig in scrotum.

- A female of the species.

- Glaive.

- Like a… No, it IS a…

Real or fanfic, 28:27

- Conor guessing

- Fanfic. ✔️ Real. ❎ Fanfic. ✔️

- Mike guessing

- Fanfic. ✔️ Fanfic. ✔️ Fanfic. ❎ Real. ✔️

Spoken word performance about “apes”: Dance, Monkeys, Dance  .

.

Ep. 13, ch. 12-15 (up to 16)

Don’t do this

- … as it came to be known. When is the narrator?

- The narrator doesn’t know what is going on.

- Calling something a fun fact, when it’s not fun. And during a serious section.

- To my surprise I did something, I’ve done many times before.

- “Boom!”

- Heavy or clumsy foreshadowing.

- Emotions bouncing around.

- 2 Star Wars references close together.

- Everything is instant. Everything is a million. Everything is exactly like… Make it smaller.

- … power lines like Godzilla. Mangled sentence.

- Is it power leap or power jump?

- Lengthy recap of battle.

- Was it my imagination? Hm.

- Keep on trucking. Anachronisms.

- Almost as if. Which I actually had. (It only feels like a simulation.)

- Zack destroys a valuable ship, and the admiral is playfully sarcastic.

- Big news, father is alive, and it’s just said, dryly. Unforced error.

- Oh, and your father is a crybaby.

- The attack is in 5 hours! Also, here’s a uniform.

- Thank Zod?

- I wish we’d met a long time ago, said the teenager.

- Token Asian.

- Pregnant pause + stand for an awkward beat.

- A talks, all the time B is chuckling.

- Stereotypes.

- … but … Not contradictory.

- Rocky Balboa does not sound like a person from Philadelphia.

- People taking forever to recognize known motion.

- Zack doesn’t recognize praying.

- Very disdainful towards religion.

- Debbie has no answer to an attack on her religion.

- Wrong name, book of revelations.

- He missed that he might die???

- Comparing a shape to Arecibo, not very well known.

- Seeing 20/20 out of the corner of his eye.

- He detects irony, but it’s also lost on him.

- Feeling like a list of things.

- Everybody’s afraid, but father is delighted.

- Sci fi theft!

- Suddenly we’re in a hurry.

- Radiant doesn’t mean that.

Running gags

- … as it came to be known.

- Pendergast.

- This is like (forgettable movie).

- Repeating information in back to back sentences.

- Pregnant pause. Cline, take it easy. Also, settle down.

- Seemed to.

- Glaive.

Oops.

- Just doesn’t like that a flier jinked.

Real or fanfic, 30:05

- Mike guessing.

- Fanfic ❎ Real ❎ Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ✔️

March 28th is Guntober.

Snake ‘n Bacon.

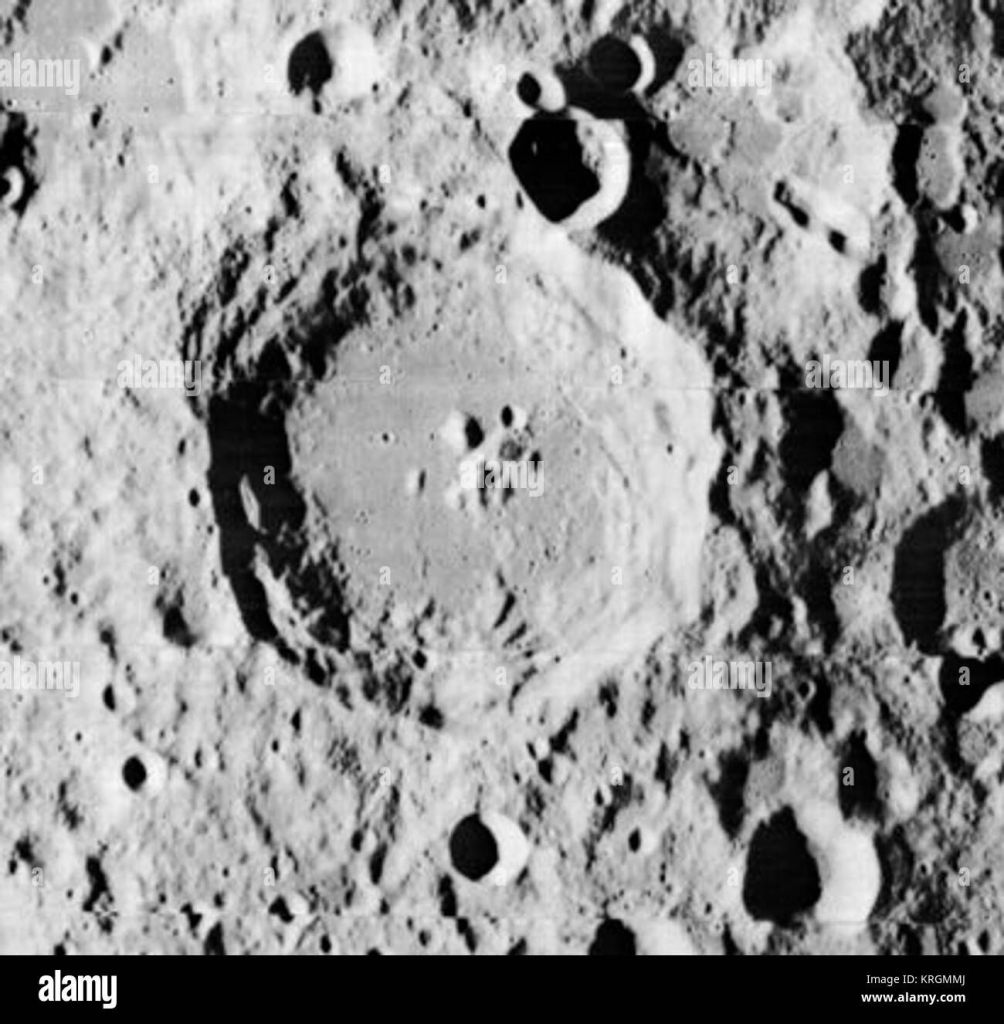

Picture of Daedalus:

Ep. 14, ch. 16-18 (up to 19)

Don’t do this

- Isolated people doing fine and making jokes.

- Overexplaining references.

- Repetition of phrases. Glance. Enormous x 2 in 1 sentence. Video.

- Stereotypical Asian.

- Being very surprised that father and son look alike.

- Suddenly sounding like Wodehouse.

- Every second counts and there’s time to talk hobbies.

- Soldiers shouldn’t have time for hobbies.

- You got my reference. Goofy grin.

- Dad’s mood swings.

- Zack can interpret all expressions.

- A list of snacks.

- Bad physical descriptions. Hard to imagine.

- The admiral is very informal.

- Zack can identify fine bone china.

- When did they see the shuttles? When they were there.

- Zack knows his own little tics.

- Even the new guy has given up on an error he just heard for the first time.

- The 3 top guys think there might be a conspiracy?

- Why all the secrecy?

- All the letters from dad are included. No surprises.

- Dad had psychological issues, but wasn’t fired.

- Star Trek and Wars are important, but neither are really about aliens invading Earth.

- Admiral Akbar famously IDENTIFIES traps.

- How to write out the Close Encounters melody.

- 250 pages. Still no plot.

- It doesn’t make sense dad makes this joke. Everybody makes the same kinds of joke all the time. Everybody’s the same person.

- Stealing valor. Quotes by great people.

Running gags

- Hot mom.

- Remember when our parents died?

Oops.

- Pronunciation of Das Boot.

- “Mispronouncing something wrong.”

- No, the episode isn’t 10 hours long.

- European/Europan.

- Yes, decahedron was corrected to dodecahedron. But it’s still described as a ten-sider with triangular faces.

- There are other ways to recognize a 20-sided shape than counting faces.

Real or fanfic, 44:22

- Mike guessing

- Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ❎ Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ❎ Fanfic ✔️ Real ❎

- Conor guessing

- Real ❎ Fanfic ❎ Fanfic ❎ ? Note that the 1st is Cline, but not Armada.

Inacronym, inaccurate acronym.

A clip will be posted, like hot dogs?

Live show coming up, will be recorded. (No, it won’t, unfortunately.)

Ep. 15, ch. 19-21 (up to phase 3)

Don’t do this

- The alien invasion still hasn’t begun!

- Keep the war on drugs going until this gamer weed is perfected.

- Not just using the word “said”.

- Mom was FOND of pointing out his gaydar was broken, OFTEN.

- Everybody’s so horny.

- How did Lex get promoted that fast?

- Gallows humor isn’t a well known word?

- Description of battle, not engaging.

- Comparing a battle to Christmas lights, popcorn and beer cans. Not very battle-y.

- Oh, it’s your first moon quake?

- I stab at thee, the Khan quote.

- Consistently calling a ship shaped like a dodecahedron a dodecahedron. It had 3 names!

- Boring: navigating through menus.

Running gags

- Golf ball atop a shot glass.

- Lag.

- Hauling ass.

Oops.

- Forgot Whoadie is a Shakespeare fan, or at least watched a lot of it.

Real or fanfic, 41:35

- Conor guessing

- Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ✔️ Real ❎

- Mike guessing

- Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ❎ Fanfic ✔️ Fanfic ❎ Real ❎

Ep. 16, ch. 22-end

Don’t do this

- Rushed chapters, abrupt ending.

- A lot happens in 1 sentence, could be a separate book.

- Lex ex machina.

- Happily nodding while so many people just died.

- Not checking the gym for people before shooting the roof.

- Long fingers. (Zack’s mom.)

- Repetition of words. Contorted (face). That playlist.

- “Is that a tricorder?” End scene.

- Being reminded of something that is exactly the same.

- Being impressed by HD. On a small screen.

- It makes no sense, I understand it perfectly.

- Blushing visibly.

- How rankings work.

- Screaming for a long time.

- And that was all it took.

- Seconds later: Reports are coming in.

- Cliché ending.

- Society is mentioned, but it was actually 3 people.

- The swastika in the beginning was stupid.

- In 1 sentence: Clean abundant energy. Cures for cancer.

Running gags

- Goods and services.

- Long fingers.

- Hot mom.

- Remember when our parents died?

![]() .) Og et forkert gæt på en bogtitel. (Deltageren gættede B, det var C.)

.) Og et forkert gæt på en bogtitel. (Deltageren gættede B, det var C.)