This week the #puzzle is: Can You Shovel the Snow? #geometry #area #equidistant #probabilities #coding #montecarlo

| Two teams of shovelers plan to remove all the snow from a parking lot that’s shaped like a regular hexagon. Team Vertex initially places each of its six shovelers at the six corners of the lot. Meanwhile, Team Centroid initially places all its shovelers at the very center of the lot. |

|

| Each team is responsible for shoveling the snow that is initially closer to someone on their own team than anyone on the other team. |

| What fraction of the lot’s snow is Team Centroid responsible for shoveling? |

And for extra credit:

| Having completed the shoveling of the hexagonal lot, the two teams move on to a circular lot. This time, Team Vertex initially places all their shovelers at one random point inside the circle, while Team Centroid initially places all their shovelers at one other, independently chosen random point inside the circle. (To be clear, by “random point” in the circle, I mean that the probability of being in any given region of the circle is proportional to that region’s area.) |

| As before, each team is responsible for shoveling the snow that is initially closer to someone on their own team than anyone on the other team. |

| Inevitably, one team is responsible for shoveling a greater fraction of the lot than the other. On average, what would you expect this greater fraction to be? |

Solution, possibly incorrect:

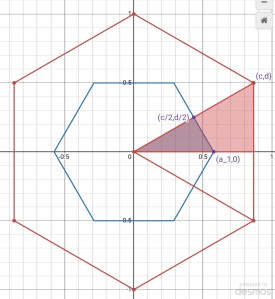

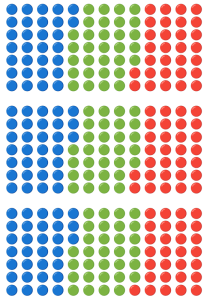

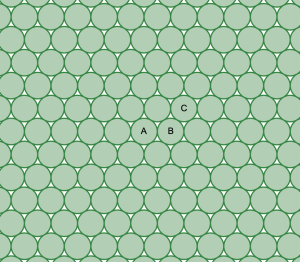

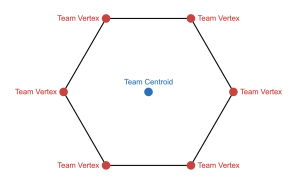

This image nicely captures my thoughts (click to enlarge):

- For each point within the hexagon, it will be closest to one particular point on the hexagon.

- The hexagon slices up into 6 parts, defined by being between 2 neighbor points on the hexagon and the center.

- On the image, a slice is shown with red borders, on the right part of the hexagon. The points on the hexagon are at (c,d) and (c,-d). c and d are calculated from the angle at the center.

- The slices are defined by lines passing through the center and a point on the hexagon.

- Within such a slice, there are further 2 halfs. In this case let’s concentrate on the upper half. In this half, points within the slice are either closer to the center or to (c,d). Find the midpoint between these 2 points and draw the perpendicular. (All the relevant perpendiculars, the parts we need at least, are drawn with blue lines.)

- On one side of the perpendicular, points are closest to the center.

- Calculate the area of the whole slice and of the purple triangle, divide, and we have our ratio.

The purple triangle is between these 3 points:

The area of the slice is:

The area of the triangle is:

The fraction of the points closest to the center:

The result is 1/3.

And for extra credit:

This could of course be solved using integrals. But I don’t know how… So I monte carlo.

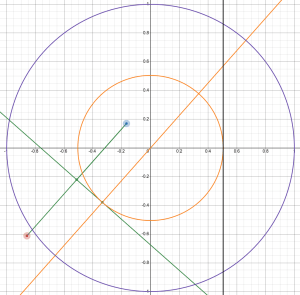

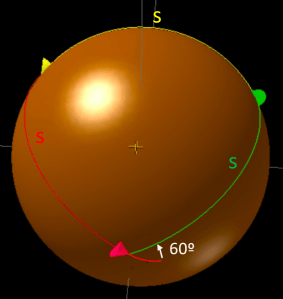

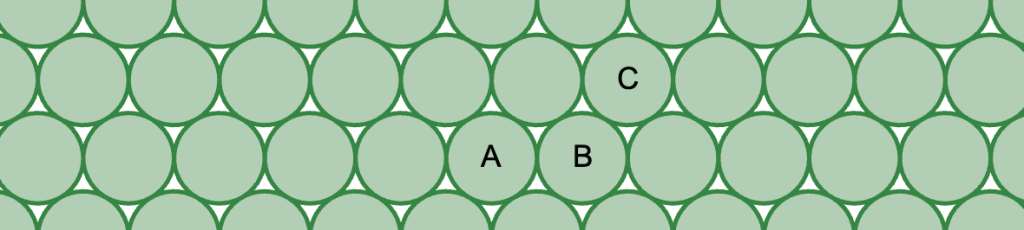

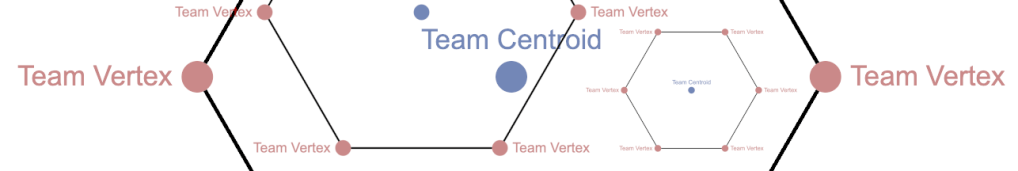

In part my program is based on what this image shows:

Given 2 random points (red and blue — the red one was trying to leave the circle there, sigh), find the midpoint between them (green). Translate the midpoint so that it’s on a line going through the center. Then rotate that new midpoint around the center, so that it lands on the x axis. Then draw the perpendicular through that point (black). Calculate the area of the circular segment on the left and calculate the fraction. (I actually calculate the smaller fraction, so it’s then subtracted from 1.)

Do this a lot of times and calculate the average.

Some of the calculations. Find the midpoint between the 2 random points:

Translate that midpoint onto the line going through the center. First find the slant of the line through the 2 random points:

Then find the translated midpoint:

Distance from translated midpoint to center:

Find angle:

Find area:

The area of the whole circle:

The fraction, remember we need the largest one:

The result, from the program, about 0.64.

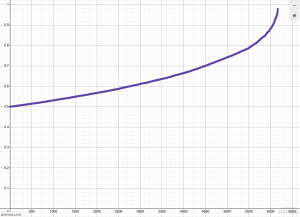

I plotted the distribution in Desmos too: