This week the #puzzle is: Some Coffee With Your Tea? #summation

| I have two glasses, one containing precisely 12 fluid ounces of coffee, the other containing precisely 12 fluid ounces of tea. |

| I pour one fluid ounce from the coffee cup into the tea cup, and then thoroughly mix the contents. I then pour one fluid ounce from the (mostly) tea cup back into the coffee cup, and then thoroughly mix the contents. |

| Is there more coffee in the tea cup, or more tea in the coffee cup? |

And for extra credit:

| I have two glasses that can hold a maximum volume of 24 fluid ounces. Initially, one glass contains precisely 12 fluid ounces of coffee, while the other contains precisely 12 fluid ounces of tea. |

| Your goal is to dilute the amount of coffee in the “coffee cup” by performing the following steps: |

| – Pour some volume of tea into the coffee cup. – Thoroughly mix the contents. – Pour that same volume out of the coffee cup (i.e., into the sink), so that precisely 12 fluid ounces of liquid remain. |

| After doing this as many times as you like, in the end, you will have 12 ounces of liquid in the coffee cup, some of which is coffee and some of which is tea. In fluid ounces, what is the least amount of coffee you can have in this cup? |

Intermission

I’m not quite sure what happened with the magic squares. I guess the method I found (writing code to calculate equations and choose among primes) didn’t work. Ah well.

I was actually part of the way with the extra credit. N has to be even. N can’t be 18 or more. But then I would have gotten it wrong, by saying N = 4 wouldn’t work.

Highlight to reveal (possibly incorrect) solution:

Thoughts:

- There’s 12 fluid ounces in each cup. There’s a coffee cup and a tea cup.

- After the mixing, the coffee cup still has 12 fluid ounces, some of it coffee, some of it tea. Let’s say the amount of coffee is c and the amount of tea is t.

- 12 = c + t.

- The tea cup has the amount 12 – c of coffee and 12 – t of tea. (The rest of the coffee and the rest of the tea.)

- How much coffee in the tea cup?

- 12 – c

- = (c + t) – c

- = c + t – c

- = t

- There’s t tea in the coffee cup and t coffee in the tea cup. The 2 amounts/ratios are the same.

And for extra credit:

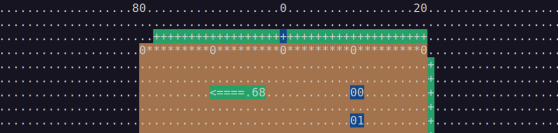

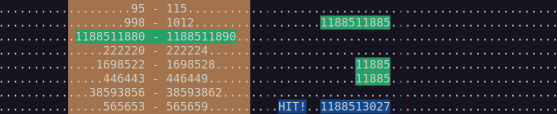

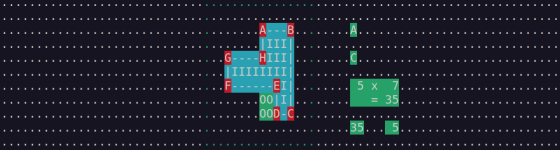

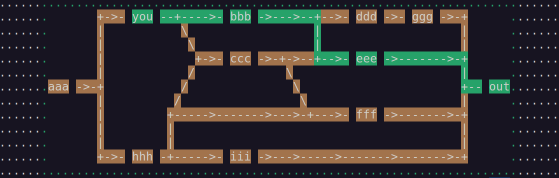

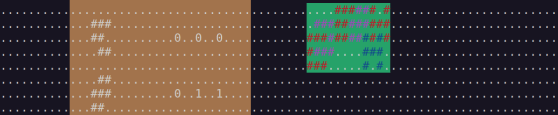

Desmos 1 ![]() 2

2 ![]()

Throughts:

- In general:

- cc0 = 12 (coffee in coffee cup to begin with)

- tc0 = f(0) (tea in coffee cup 1st time , for some function f)

- Then something is poured out.

- Δcc = cc0 * f(0) / (cc0 + tc0)

- = cc0 * f(0) / (12 + f(0))

- Δtc = tc0 * f(0) / (12 + f(0))

- cc1 = cc0 – Δcc

- = cc0 – cc0 * f(0) / (12 + f(0))

- = cc0 (1 – f(0)/(12 + f(0))

- tc1 = tc0 (1 – f(0) / (12 + f(0))

- cc2 = cc1 (1 – f(1)/(12 + f(1))

- cc0 (1 – f(0)/(12 + f(0)) (1 – f(1)/(12 + f(1))

- Example 1:

- f is always some ε, constant.

- We go n = 12 / ε rounds.

- ccn = cc0 (1 – ε/(12 + ε)n

- = cc0 (1 – ε/(12 + ε)(12/ε)

- Going to desmos, this expression has a minimum with ε approaching 0, approximately 4.41455. This looks suspiciously like 12/e. Also it’s the best option I’ve found.

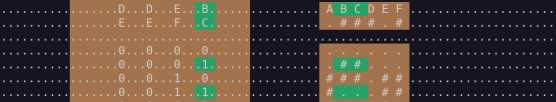

- Example 2:

- f is shrinking. E.g., it might say, that each round half the remaining pure tea is added.

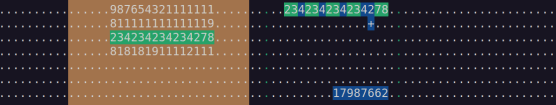

- f(0) = 12/2 = 6 = 6/20

- f(1) = f(0)/2 = 12/22 = 6/2 = 6/21

- f(n) = 6/2n

- This one goes ∞ rounds.

- cc∞ = cc0 (1 – 6/20/(12 + 6/20)) (1 – 6/21/(12 + 6/21)) (1 – 6/22/(12 + 6/22)) … (1 – 6/2∞/(12 + 6/2∞))

- 1 – 6/20/(12 + 6/20)

- = (12 + 6/20)/(12 + 6/20) – 6/20/(12 + 6/20)

- = (12 + 6/20 – 6/20)/(12 + 6/20)

- = 12/(12 + 6/20)

- = (6 * 2)/(6 * (2 + 2-0))

- = 2 / (2 + 2-0)

- cc∞ = cc0 (2 / (2 + 2-0)) (2 / (2 + 2-1)) (2 / (2 + 2-2)) … (2 / (2 + 2-∞))

- = cc0 * 2/3 * 4/5 * 8/9 * … 1

- Using Desmos, cc∞ = cc0 * 0.41942 = 12 * 0.41942 = 5.03307

- There might be a shrinking strategy, that works better, but this one gave a worse result than using a constant.

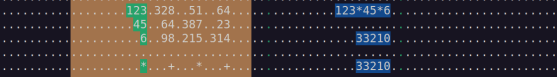

- Just for fun I tried adding 2/3 of the pure tea instead of 1/2. Now cc∞ = cc0 * 0.44058 = 12 * 0.44058 = 5.28696. Worse. 3/4 is even worse.

- I haven’t gone through all the possible strategies, because it’s hard to find a systematic way to do this.