This week the #puzzle is: Bingo! #statistics #probabilities #combinatorics #counting #coding #program #montecarlo

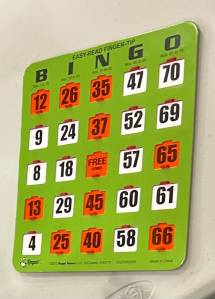

| A game of bingo typically consists of a 5-by-5 grid with 25 total squares. Each square (except for the center square) contains a number. When a square’s number is called, you place a marker on that square. The goal is to get “bingo,” which is five squares in a row, either across, down, or along one of the two long diagonals. The center square, which doesn’t have a number, is labeled “Free,” and begins with a marker on it before any numbers are called. Here’s an example of a winning 5-by-5 grid in which 10 squares (other than the “Free” square) have been marked: |

|

| Consider a smaller version of the game with a 3-by-3 grid: a “Free” square surrounded by eight other squares with numbers. Suppose each of these eight squares is equally likely to be called, and without replacement (i.e., once a number is called, it doesn’t get called again). |

| On average, how many markers must you place until you get “bingo” in this 3-by-3 grid? (The “Free” square doesn’t count as one of the markers—it’s “free”.) |

And for extra credit:

| Instead of a 3-by-3 grid, let’s return to the original 5-by-5 grid. |

| On average, how many markers must you place until you get “bingo”? (As before, the “Free” square doesn’t count as one of the markers—it’s “free”.) |

Highlight to reveal (possibly incorrect) solution:

Method 1: Monte carlo. See program.

Method 2: Go through all options. See program.

Method 3: Go through all options by hand.

Result: 3.471429 markers.

And for extra credit:

Method 1 and 2, from above.

Result: 13.608084 markers.

I had to optimize the program quite a lot to get a reasonable run time. Memoization. And taking into account, that each setup exists in 8 versions, rotated and mirrored. As always it’s a joy when a recursive function suddenly works.