This week the question is: Can You Win at “Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock?”

In a game of “Rock, Paper, Scissors,” each element you can throw ties itself, beats one of the other elements, and loses to the remaining element. In particular, Rock beats Scissors beats Paper beats Rock.

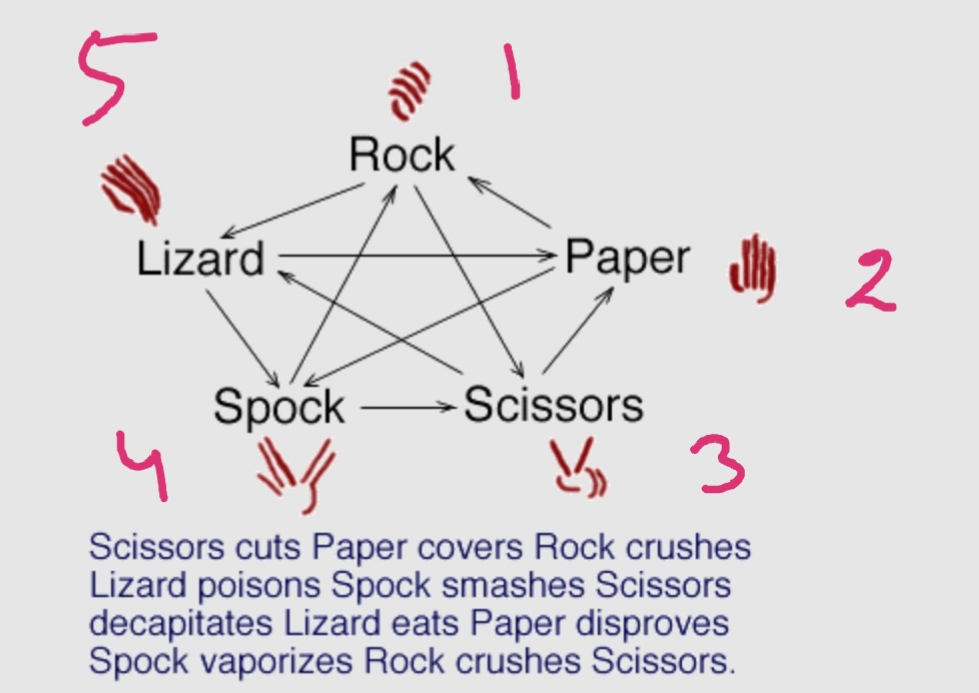

“Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock” (popularized via The Big Bang Theory) is similar, but has five elements you can throw instead of the typical three. Each element ties itself, beats another two, and loses to the remaining two. More specifically, Scissors beats Paper beats Rock beats Lizard beats Spock beats Scissors beats Lizard beats Paper beats Spock beats Rock beats Scissors.

Three players are playing “Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock.” At the same time, they all put out their hands, revealing one of the five elements. If they each chose their element randomly and independently, what is the probability that one player is immediately victorious, having defeated the other two?

And for extra credit:

The rules for “Rock, Paper, Scissors” can concisely be written in one of the following three ways:

- Rock beats Scissors beats Paper beats Rock

- Scissors beats Paper beats Rock beats Scissors

- Paper beats Rock beats Scissors beats Paper

Each description of the rules includes four mentions of elements and three “beats.”

Meanwhile, as previously mentioned, a similarly concise version of the rules for “Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock” (and adapted from the original site) is:

- Scissors beats Paper beats Rock beats Lizard beats Spock beats Scissors beats Lizard beats Paper beats Spock beats Rock beats Scissors

In this case, there are 11 mentions of elements and 10 “beats.” Including the one above, how many such ways are there to concisely describe the rules for “Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock

For my own sanity:

Highlight to reveal (possibly incorrect) solution:

Using the numbers shown above, 1 beats 3 and 5. In general, n beats n+2 and n+4, mod 5. This will be useful for the program.

Given 3 players (A, B and C), we might have one absolute winner, one absolute loser without an absolute winner, a circle (everybody wins once and loses once) and a threeway tie.

| A | B | C | Result |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Tie! |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | C wins |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | C loses |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | C wins |

| 1 | 1 | 5 | C loses |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | B wins |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | A loses |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Circle |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | B wins |

| 1 | 2 | 5 | Circle |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | B loses |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | Circle |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | A wins |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | C wins |

| 1 | 3 | 5 | A wins |

WLOG, simply assume A chose 1. The table above could be duplicated a bit, because B choosing either 2 or 4 is equivalent, and the same for B choosing either 3 or 5. When B chooses 1, there’s a 2/5 chance for an absolute winner. When B chooses 2 or 4, there’s a 2/5 chance for an absolute winner. When B chooses 3 or 5, there’s a 3/5 chance for an absolute winner. Added up, this is a (2+2*2+2*3)/25 = 12/25 = 48% chance for an absolute winner. The program confirms this.

And for extra credit:

I go through all the ways to traverse the graph shown above, using each edge once. Each way corresponds to a new way to write out the long sentence with a beats b etc. My program finds 22 different ways to begin at 1. This gives 110 ways in all.