This week the question is: Can You Make a Toilet Paper Roll?

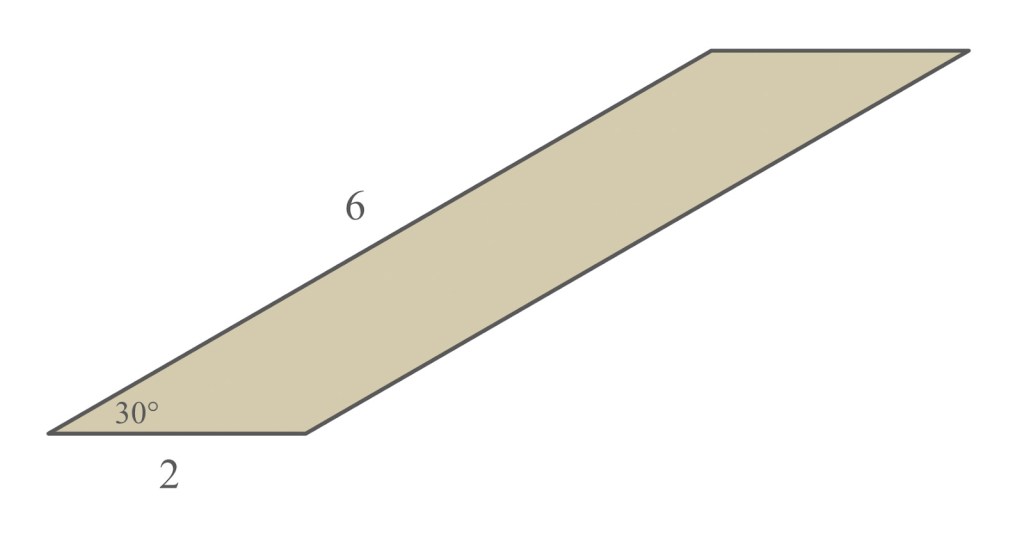

Suppose you have the parallelogram of cardboard shown below, which has side lengths of 2 units and 6 units, and angles of 30 degrees and 150 degrees:

By swirling two edges together, it’s possible to neatly (without any overlap) generate the lateral surface of a right cylinder—in other words, a toilet paper roll! (If you’re not convinced, try gently tearing a toilet paper roll along its diagonal seam and then unwrapping it into a flat shape. You get a parallelogram!)

Determine the volume of a cylinder you can make from this particular piece of cardboard.

And for extra credit:

Suppose you have a parallelogram with an area of 1 square unit. Let V represent the average volume of all cylinders whose lateral surface you can neatly make by swirling two edges of the parallelogram together.

What is the minimum possible value of V?

Highlight to reveal solution:

Figure 1 shows, that if I construct my cylinder the traditional way, it will have a base with circumference 2. Therefore the radius of the base will be 2/2π = 1/π. Meanwhile the height h of the cylinder depends on x. The pink triangle demonstrates, that the length of the long edge, 2x, gives a height of x. 2x = 6 <=> x = 3. This means the volume of the cylinder is πr2h = π(1/π)2*3 = 3/π, about 0.955.

But there’s another way to construct a cylinder. The base could have circumference 6. (It would end up tilted in space, where the first one rests nicely on its base.) This base has radius 6/2π = 3/π. The green triangle shows, that the height h of this cylinder is y, and 2y = 2 <=> y = 1. The volume of this cylinder is πr2h = π(3/π)2*1 = 9/π, about 2.865.

The way this riddler is worded, both solutions should be valid.

This seems too easy! Like there are other solutions. But for now, these should be 2 valid solutions.

And for extra credit:

Calculation sheet 1 and 2. Wolfram Alpha result.

Let’s do the whole thing in more general terms. The parallelogram has sides a and b, a >= b, and angle α. b corresponds to height h1, a corresponds to height h2. In a small triangle, I have sides a*, b and h*. Further sin(α)/h* = sin(90°-α)/b = sin(90°)/a*. Rearranging gets h* = b * sin(α)/sin(90°-α) and a* = b * 1/sin(90°-α). Also, h1/h* = a/a* <=> h1 = h* * a/a* = b * sin(α)/sin(90°-α) * a * sin(90°-α)/b = sin(α) * a.

For symmetry reasons, h2 = sin(α) * b.

(Sanity check: a = 6, b = 2, α = 30°. h1 = sin(30°) * 6 = 0.5 * 6 = 3. h2 = sin(30°) * 2 = 0.5 * 2 = 1. Same result as before.)

The first cylinder has circumference b, radius b/2π, height h1 = sin(α) * a, volume πr2h = π * (b/2π)2 * sin(α) * a = b2 * a / 4π * sin(α). The other has circumference a, radius a/2π, height h2 = sin(α) * b, volume πr2h = π * (a/2π)2 * sin(α) * b = a2 * b / 4π * sin(α).

Let’s take the average of these two: (b2 * a / 4π * sin(α) + a2 * b / 4π * sin(α))/2 = (b2 * a + a2 * b) * sin(α)/8π. And let’s try to minimise it. 8π is a constant and can be thrown away. Minimise (b2 * a + a2 * b) * sin(α).

The area of the parallelogram is 1. b * h1 = a * h2 = 1. From what we know about the heights, b * sin(α) * a = a * sin(α) * b = 1 <=> ab = 1/sin(α).

We’re minimising (b2 * a + a2 * b) * sin(α) = ab * (b + a) * sin(α) = 1/sin(α) * (b + a) * sin(α) = b + a. Using the expression for ab one more time, we’re minimising a + 1/(sin(α)*a). A quick trip to Wolfram Alpha later, and we find a minimum at a = 1, α = 90°, hence also b = 1. So min(a + b) = 2, and this occurs when the parallelogram is actually a square. ETA: Therefore the volume is 2/8π, approximately 0.0796.

All of this still based on: Every parallelogram can be turned into at most 2 cylinders.

And previously:

I didn’t get around to doing the fiddler last week. But it turns out I had the right idea. Here’s a sketch.

Denote the state of the tiles like this: xxxxxx. This means all 6 tiles have been flipped, and I won.

If the state is 1xxxxx, and I roll a 1, I win, otherwise I lose. So in this state p(win) = 1/6.

Similarly for x2xxxx, xx3xxx etc.

If the state is 12xxxx, and I roll a 1, move on to x2xxxx. Roll a 2 and move to 1xxxxx. Roll a 3 and win. Otherwise lose. Here p(win) = 1/62 + 1/62 + 1/6 = 8/36 = 2/9.

If the state is 123xxx, and I roll a 3, I have a choice. If I flip 1 and 2, I move to xx3xxx and p(win) = 1/6. If I flip 3, I move to 12xxxx and p(win) = 2/9. So the optimal strategy is to flip 3.

Build a big table with all the states and all the probabilities and all the rolls. Begin with 6 flipped tiles, then 5 flipped tiles etc. Every time a roll gives me more than 1 choice, consider p(win) for the states, I can go to, choose the best one and make a note of it. My optimal strategy is all these good choices.

Finally I can read in this table what p(win) is for the state 123456. And that’s the probability I’m looking for.

The extra credit version has 9 tiles and 2 dice. Otherwise it’s the same procedure.